This article by John Tatlock does a good job at articulating the differences in the new Twin Peaks iteration without going into spoilers. I won't go into too many details, but here are some semi-spoilerish thoughts on what exactly is happening with Twin Peaks and why this is what we are getting in 2017 (and don't expect that to change any time soon).

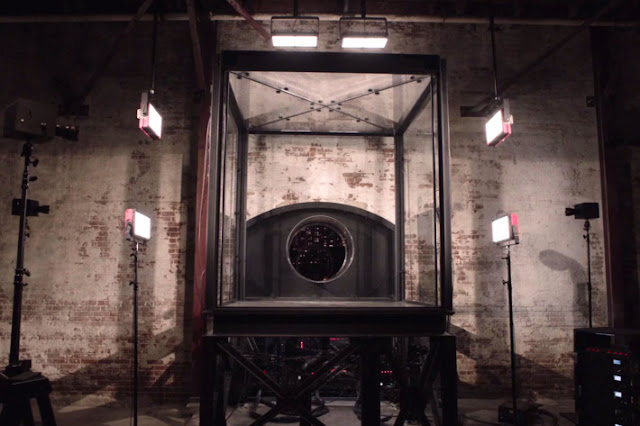

It becomes pretty clear by the time Brett Gelman and Michael Cera arrive on screen in episode 4 that Lynch is making this show in full awareness of the Adult Swim roster, much of which thrived on a surreal horror-comedy that was clearly in debt to Lynch himself. In fact, there's an acknowledgment of many items that have trickled through the TV/film matrix both over the last 25 years and prior. It’s unclear if distracting allusions to the Addams Family and The Wild One are inserted to be canny, clever, or intentionally awkward, but they play as the latter. Just as the tonal shift of the Twin Peaks film was announced with its opening shot of a TV screen being smashed (and then with an FBI agent making vague threats to "Deputy Cable"), the new series, available as a TV Show, streaming show, or, at a later date, as an 18 hour movie, seems to just be trapped somewhere in a virtual consciousness, figuring itself out. One of the major plot points in episode one concerns a giant unexplained glass cage based out of TV capital NYC which has no known origin or originator- it's a literal manifestation of a mystery box, the genre Twin Peaks helped to create (though the mystery in the box was never intended to be solved- for further physical manifestations of this, see Westworld's McGuffin map).

The series takes place in a world in which language and communication have become so corrupted that the mere concept of rational thought and dialogue seems like an impossibility. The show's initial concern is returning Cooper from the Black Lodge, but something from that world seems to be infecting everything outside of it. Gone is the witty banter and maudlin lovelorn confessions of the initial series. Instead, there are impossibly long pauses, stunted phrases, and often stupid, just plainly and hopefull-intentionally idiotic back and forths. One can pull from this tenuous narrative gauze a potential thought project about aging. The geriatric experience is made manifest in the slow processing of language, the way characters have to repeat themselves, and the deep frustration that comes from realizing that even utilizing filters like repetition and drawn-out-speech does not clear the deep confusion of existence. The whole thing seems like a product of dementia or senility (in fact, Cooper is probably suffering from it), a borderline sensibility that Lynch no doubt realizes will be leveled against him by his harshest critics. Indeed, reuniting much of the old cast, many of whom were already in late adulthood when the show first aired over 25 years ago, finds a number of them missing- Miguel Ferrer, Jack Nance, Frank Silva, David Bowie, Warren Frost, Don Davis, and Catherine Coulson have all passed away in recent years. If the initial run was about youth and the uncomfortable proximity between rebellion against adulthood and total corruption into its darker tenets (as personified in Laura Palmer, but elsewhere as well), the renewed series has thus far focused on the cold, empty, and lonely terror of old age.

Fittingly for a Lynch piece, the old cast of characters reappear but like dream caricatures of themselves. Albert doesn't talk much and yet seems crankier than usual. Andy is now almost too dumb. Dr. Jacoby is now clearly insane, collecting and decorating golden shovels either in anticipation of digging something up or burying something deep. Lynch himself appears (in episode 4), revising his role as Gordon, to talk to a version of Cooper. They both tell each other that's it's been great to see each other after such a long time, but it's obvious in their strained chat that neither of them is being honest. Lynch, as Gordon and - mind you- the director and author of the whole new series run- later becomes the only voice of levity when he confesses that perhaps for the first time, he has no idea what the hell is happening. Should we take this as a confession? So much of this show reads as auto-critique, attempts to negotiate itself in the most Lynchian way, as a piece of intellectual property. What people want, it assumes, is something old and dying, malfunctioning and regressive. What it has to offer as an alternative, however, remains to be seen.